Rara placchetta in bronzo raffigurante un Compianto

English version above

di Attilio Troncavini

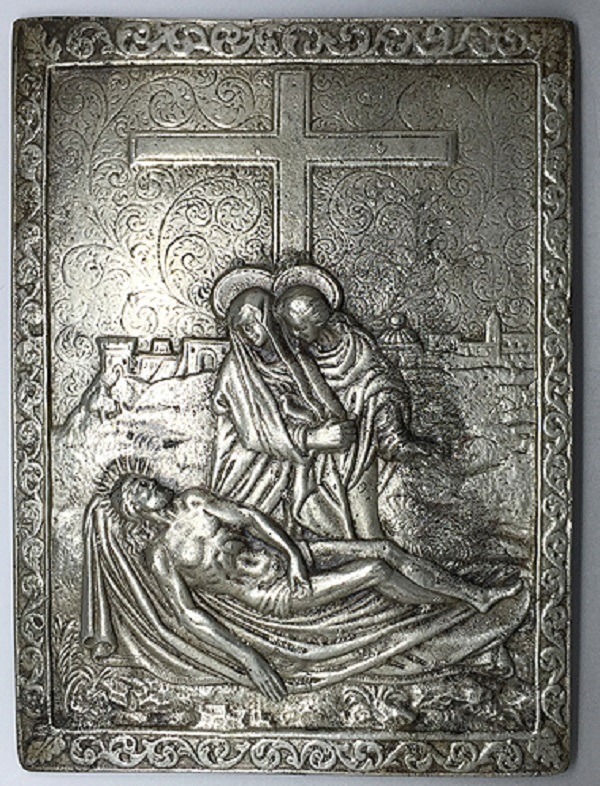

Sono anni che studio questa placchetta un bronzo [Figura 1] senza riuscire a determinarne con esattezza epoca e provenienza e nemmeno a ipotizzare a quali fonti iconografiche l’autore si possa essere ispirato (nota 1).

Figura 1. Artefice ignoto, Compianto, bronzo, cm. 15,5 x 11,5, fine XVI secolo, Milano, collezione privata.

Il Cristo è deposto su un lenzuolo con le gambe incrociate e le braccia abbandonate lungo il corpo; la testa è contornata da un’aureola raggiata. Su di lui incombono le figure molto ravvicinate dei Dolenti, Maria e Giovanni; sembra di vedere che Maria intrecci le mani spostandole verso la sua sinistra (nota 2). Alle loro spalle si erge una Croce “metafisica” che ricorda quella che compare in alcune placchette della Pietà attribuite a Jacopo e/o Ludovico del Duca (nota 3); infine, sullo sfondo, si vedono una rocca, un arco antico, una cupola, delle mura e un campanile che rappresentano una città ideale non identificabile.

Riprendo il discorso sia perché, nel frattempo, è emersa una piccola novità, sia perché spero sempre che dal pubblico dei visitatori, in questo caso allargato, complice una traduzione in inglese, possa scaturire qualche segnalazione utile.

A suo tempo ne avevo discusso con Mike Riddick, studioso ed esperto di bronzi rinascimentali il cui sito www.renbronze.com non perdiamo mai occasione di raccomandare.

Ecco cosa scriveva, in sintesi, Riddick nel 2015 (comunicazioni personali via mail): “di questa placchetta si conoscono solo altri quattro esemplari e quella in discussione è probabilmente la versione più antica; le placchette note si trovano tutte in collezioni private, in qualche caso dopo essere transitate sul mercato delle aste e non risulta che alcun museo ne possieda un esemplare”.

La prima viene giudicata una fusione più tarda, realizzata, diversamente dalle altre, in una lega di colore chiaro [Figura 2].

Figura 2. Artefice ignoto, Compianto, lega metallica, collezione privata (già collezione Mike Riddick).

Le altre, di cui non mostriamo le immagini per la cattiva qualità delle stesse, tutte molto simili a quella di Figura 1, provengono rispettivamente da un’asta del 9-10 giugno 1997 n. 2066 di una casa d’Aste non identificata, ivi classificata come italiana del XVI secolo, dall’asta Bonhams del 9 dicembre 2009, n. 144 (cm. 16,5 x 12), ivi classificata come spagnola del XVII secolo e dall’asta Wannenes, 3 marzo 2015 n. 24 (già Collezione Vivioli).

Riddick concorda sull’epoca, ossia sulla fine del XVI secolo, e sul fatto che le placchette possano essere italiane con possibili influenze fiamminghe.

A questo esiguo catalogo si aggiungono due placchette apparse entrambe sul mercato antiquario: la prima nel 2018 [Figura 3], la seconda nel 2019 in pendant con una celebre placchetta che si deve al Moderno (nota 4), entrambe all’interno di cornici ottocentesche in pastiglia dorata. La “coppia” era stata proposta in asta nel 2017 presso Poggio Bracciolini come frutto di una fusione ottocentesca [Figura 4].

Figura 3. Artefice ignoto, Compianto, bronzo, cm. 16,5 x 12, fine XVI secolo, mercato antiquario.

Figura 4. Artefice ignoto, Compianto e Flagellazione (copia da Moderno), bronzo, XIX secolo, mercato antiquario, già Poggio Bracciolini 6.12.17 n. 383.

Sono nell’impossibilità di valutare se le placchette di cui alla Figura 4 siano effettivamente ottocentesche o meno – mi fido dell’esperienza dei responsabili della casa d’Aste Poggio Bracciolini.

Sicuramente gli esemplari del Compianto in discorso non sono in alcun modo attribuibili al Moderno per cui la “coppia” è stata composta per quelle che venivano ritenute delle affinità stilistiche – cui può anche aver contribuito anche la riquadratura – completando l’opera inserendole in uno stesso tipo di cornice dorata.

Si è allora tentato di trovare per il nostro Compianto qualche confronto in altre placchette.

Quella che più si avvicina è una placchetta attribuita a Giovanni Battista Scultori (1503-1575) [Figura 5, nota 5]. Tuttavia, a parte lo stesso soggetto e la posizione di Giovanni con il braccio teso all’indietro, non sembra di ravvisare alcuna affinità né sul piano stilistico, né su quello esecutivo.

Figura 5. Giovanni Battista Scultori (attr.), Deposizione, argento dorato, cm. 11,7 x 7,5, collezione Scaglia.

La “novità” a cui alludevo all’inizio è la scoperta di una placchetta – che sarebbe forse più corretto definite un rilievo – presso un museo californiano [Figura 6].

Figura 6. Cristo portacroce, bronzo, cm. 15,9 x 12,3, seconda metà del XVI secolo, Santa Barbara AD&A Museum UC, inv. 1964.574, provenienza: Collezione Sigmund Morgenroth.

Sebbene in controparte, il gruppo costituito da Maria e da Giovanni è molto simile a quello della placchetta di Figura 1 [Figure 1a e 6a].

Figura 6a. Cristo portacroce, Santa Barbara AD&A Museum UC (particolare della Figura 6).

Figura 1a. Deposizione, Collezione privata (particolare della Figura 1 capovolto in senso orizzontale).

Purtroppo, questa notizia non ci fa progredire di molto nella ricerca perché il museo di Santa Barbara, pur confermando una datazione alla seconda metà del Cinquecento, non azzarda ipotesi circa l’ambito di provenienza geografica o il possibile artefice (“artist unkniwn”).

Il fatto che la coppia di figure accostate sia in controparte può far pensare che una delle due sia stata tratta da un’incisione in cui l’altra sia stata in precedenza tradotta.

NOTE

[1] Sul retro era stata applicata un’etichetta manoscritta con scrittura novecentesca, ora rimossa, in cui si leggeva: “Italia nord orientale / seconda metà del XVI sec. / cfr: Imbert tav. VI 2 / – Finarte Asta 909 / ottobre 94 n. 57 / valutaz. 1,8-2,4”, scritta rivelatasi fuorviante. La scritta ripropone la didascalia del catalogo Finarte, ma né il lotto 57, né l’esemplare già in Collezione Imbert corrispondono alla placchetta in questione. Sull’antiquario Imbert si possono leggere gli articoli Eugenio Imbert collezionista e antiquario (febbraio 2021) [Leggi] e Eugenio Imbert collezionista e antiquario. I fotografi (maggio 2021) [Leggi].

[2] Il gesto ricorda la celebre Pietà di Sebastiano del Piombo per la chiesa di San Francesco a Viterbo e ora al Museo Civico di Viterbo (sede staccata presso il palazzo dei Priori), da un’idea elaborata da Michelangelo – impiegata per la Rachele della tomba di Giulio II a Roma – che lo stesso Michelangelo pare abbia mutuato dai Compianti emiliani quattrocenteschi. Ritroviamo questo gesto variamente interpretato, in molte raffigurazioni, ma desidero qui citare due sculture di Orazio Marinali, una Pietà (1687-89) per la chiesa di san Vincenzo a Vicenza (1687-89) e un’Addolorata (1708) per la chiesa dei Margheritoni di Arcugnano (Vi).

[3] Si rimanda all’articolo Michelangelo’s Pieta in Bronze (novembre 2016) [Leggi] e agli altri ivi richiamati.

[4] Su questa placchetta si rimanda agli articoli apparsi su Antiqua: La Flagellazione del Moderno e Michelangelo (ottobre 2018) [Leggi] e La Flagellazione del Moderno (segue) (novembre 2018) [Leggi].

[5] L’attribuzione si deve a Francesco Rossi, secondo il quale la placchetta sarebbe ricavata da un rilievo in argento commissionato nel 1562 a Giovanni Battista Scultori da Ippolito Capilupi, vescovo di Fano e Nunzio Apostolico a Venezia, inserito in una cornice commissionata dal duca Guglielmo Gonzaga entro il 1562, facente parte del Tesoro della Basilica di Santa Barbara a Mantova e dal 1983 conservata presso il locale Museo Diocesano [Figura A] (Rossi Francesco, La collezione Mario Scaglia. Placchette, Lubrina, Bergamo 2011, p. 383-384, ill. X.20 p197 tav. LXXV).

Figura A. Giovanni Battista Scultori (attr.), Deposizione, argento, Mantova, Museo Diocesano.

Ottobre 2022

© Riproduzione riservata

Rare bronze plaquette depicting a Lamentation

by Attilio Troncavini

I have been studying this bronze plaquette [Fig. 1] for years without being able to determine its exact age and origin, nor to hypothesize which iconographic sources the author may have been inspired by (note 1).

Fig. 1. Artist unknown artificer, Lamentation, bronze, cm. 15.5 x 11.5, late 16th Century, Milan, private collection.

Christ is placed on a sheet with his legs crossed and his arms abandoned along the body; the head is surrounded by a rayed halo. The very close figures of the Mourners, Mary and John loom over him; it seems to see that Maria intertwines her hands, moving them to her left (note 2). Behind them stands a “metaphysical” Cross that recalls the one that appears in some plaques of the Pietà attributed to Jacopo and / or Ludovico del Duca (note 3); finally, in the background, you can see a fortress, an ancient arch, a dome, walls and a bell tower that represent an unidentifiable ideal city.

I will resume the discussion both because, in the meantime, a small novelty has emerged, and because I always hope that some useful information may arise from the public of visitors, in this extended case, thanks to an English translation.

At the time I had discussed it with Mike Riddick, a scholar and expert in Renaissance bronzes whose site www.renbronze.com we never miss an opportunity to recommend.

Here is what Riddick wrote in summary in 2015 (personal communications via e-mail): only four other examples of this plaquette are known and the one under discussion is probably the oldest version; the known plaquettes are all found in private collections, in some cases after passing through the auction market and it does not appear that any museum possesses an example.

The first is judged to be a later casting, made, unlike the others, in a light-colored alloy [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2. Artist unknown, Lamentation, metal alloy, 17th Century (?), private collection (formerly Mike Riddick collection).

The others, the images of which we do not show due to their poor quality, all very similar to that of Fig. 1, come respectively from an auction of 9-10 June 1997 no. 2066 of an unidentified auction house, there classified as Italian of the sixteenth century, by the Bonhams auction of 9 December 2009, no. 144 (16.5 x 12 cm), there classified as Spanish of the seventeenth century and from the Wannenes auction, March 3, 2015 no. 24 (formerly the Vivioli Collection).

Riddick agrees on theage, ie the end of the sixteenth century, and on the fact that the plaquette may be Italian with possible Flemish influences.

To this small catalog are added two plaquettes both appeared on the antiques market: the first in 2018 [Fig. 3], the second in 2019 in pendant with a famous plaquette due to the Moderno (note 4), both inside nineteenth-century frames in golden tablet. The “couple” was offered at auction in 2017 at Poggio Bracciolini as the result of a nineteenth-century merger [Fig. 4].

Figure 3. Artist unknown, Lamentation, bronze, cm. 16.5 x 12, late 16th century, antiques market.

Figure 4. Artist unknown craftsman, Lamentation and Flagellation (copy from Moderno), bronze, 19th century, antiques market, formerly Poggio Bracciolini 6.12.17 n. 383.

I am unable to assess whether the plaques in Fig. 4 are actually nineteenth-century or not – I trust the experience of the managers of the Poggio Bracciolini auction house.

Surely the examples of the Lamentation in question are in no way attributable to the Modern for which the “couple” was composed for what were considered stylistic affinities – to which the framing may also have contributed – completing the work by inserting them in the same type of golden frame.

We then tried to find some comparisons for our Lamentation in other plaquettes.

The one that comes closest is a plaquette attributed to Giovanni Battista Scultori (1503-1575) [Fig. 5, note 5]. However, apart from the same subject and Giovanni’s position with his arm stretched back, it does not seem to recognize any affinity either on a stylistic or executive level.

Fig. 5. Giovanni Battista Scultori (attr.), Lamentation, gilded silver, cm. 11.7 x 7.5, Scaglia collection.

The “novelty” I alluded to at the beginning is the discovery of a plaquette – which would perhaps be more correct to define a relief – at a Californian museum [Fig. 6].

Fig. 6. Christ carrying the cross, bronze, cm. 15.9 x 12.3, second half of the 16th century, Santa Barbara AD&A Museum UC, inv. 1964.574, Provenance: Sigmund Morgenroth Collection.

Although on the other hand, the group consisting of Mary and John is very similar to that of the plaquette of Fig. 1 [Fig. 1a and 6a].

Fig. 6a. Christ carrying the cross, Santa Barbara AD&A Museum UC (detail of Figure 6).

Fig. 1a. Lametation, private collection (detail of Fig. 1 upside down horizontally).

Unfortunately, this news does not make us progress much in research because the Santa Barbara museum, while confirming a dating to the second half of the sixteenth century, does not venture hypotheses about the geographical area of origin or the possible author (“artist unkniwn”).The fact that the pair of figures juxtaposed is in counterpart may suggest that one of the two was taken from an engraving in which the other was previously translated.

NOTE

[1] On the back a handwritten label with twentieth-century writing had been applied, now removed, which read: “Northeastern Italy / second half of the sixteenth century. / cf: Imbert pl. VI 2 / – Finarte Auction 909 / October 94 n. 57 / evaluation 1,8-2,4 ”, written that turned out to be misleading. The writing reproduces the caption of the Finarte catalog, but neither lot 57 nor the specimen already in the Imbert Collection correspond to the plaque in question. On the Imbert antiquarian you can read the articles Eugenio Imbert collector and antiquarian (February 2021) [Read] and Eugenio Imbert collector and antiquarian. The photographers (May 2021) [Read].

[2] The gesture recalls the famous Pietà by Sebastiano del Piombo for the church of San Francesco in Viterbo and now at the Civic Museum in Viterbo (palazzo dei Priori), from an idea developed by Michelangelo – used for the Rachel of the tomb of Julius II in Rome – that the same Michelangelo seems to have borrowed from the 15th-century Emilian “Compianti”. We find this gesture variously interpreted, in many representations, but here I would like to mention two sculptures by Orazio Marinali, a Pietà (1687-89) for the church of San Vincenzo in Vicenza (1687-89) and an Addolorata (1708) for the church of the Margheritoni of Arcugnano (Vi).

[3] Please refer to the article Michelangelo’s Pieta in Bronze (November 2016) [Read] and the others mentioned therein.

[4] On this plaqueyye, please refer to the articles published in Antiqua: The Flagellation of the Modern and Michelangelo (October 2018) [Read] and The Flagellation of the Modern (continued) (November 2018) [Read].

[5] The attribution is due to Francesco Rossi, according to whom the plaquette is obtained from a silver relief commissioned in 1562 to Giovanni Battista Scultori by Ippolito Capilupi, bishop of Fano and Apostolic Nuncio in Venice, inserted in a frame commissioned by Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga by 1562, part of the Treasury of the Basilica of Santa Barbara in Mantua and since 1983 kept in the local Diocesan Museum [Fig. A] (Rossi Francesco, La collezione Mario Scaglia. Placchette, Lubrina, Bergamo 2011, p. 383-384, ill. X.20 p197 tav. LXXV.

Fig. A. Giovanni Battista Scultori (attr.), Lametation, silver, Mantua, Diocesan Museum.